Conversations

Steve Chilton

Established in 2015, SCA | Steven Chilton Architects is a London-based group of highly skilled practitioners connecting cultural insight and the creative use of technology to achieve an unexpected architecture that seeks to embrace, captivate and surprise.

We spoke with Steven Chilton in London - working from home like many others in his profession - and asked him about his projects, his practice, and the challenges and opportunities he sees for architectural design.

Have you been back to China since the pandemic?

I haven’t, no. It has recently opened up, and if something comes up I’d love to go back and have a look around and see how the buildings are looking. A couple of our projects I haven’t actually seen finished. We’ve obviously still been involved and have overseen the completions, but we haven’t seen them in person yet.

Is that the Guangzhou Theater? That’s a striking building, isn’t it?

That was something new. We haven’t produced such a three-dimensional amorphous object before and so it was pretty challenging. It was made to, we hoped, look like a piece of twisted silk. But translating the concept into 3d information, which then people can go away and actually build from, was interesting and certainly pushed our capabilities.

The feedback we’ve had is the quality of the cladding in particular is exceptional. That’s primarily down to the contractor and the guys on the ground, obviously. We’re happy that the information we were able to produce for them worked out, because it was our first time.

A lot of architects are moving more to 3D modeling, to try and get an understanding of how things piece together. Is that something you’re doing?

Yes, we’ve done a certain amount of 3D printing to test concepts and to look mainly at details at a scale which allows us to understand them a bit more and how they come together.

With regards to looking at ideas at a conceptual level and testing them, we’re currently more involved in using software - Unreal Engine in particular - for realtime rendering. We create a 3D model in a traditional program such as Rhino, then bring it into Unreal Engine and put materials on it, put lighting on it, and manipulate it and spin it around and see it in three dimensions almost photo-realistically in a matter of

minutes. Four or five years ago that would’ve been a challenge.

The tech is moving so fast and the possibilities that opens up for us as designers are so exciting. We try and keep up with these technologies, and I can see us really harnessing that one in particular for our future work.

What would you as a young architecture student have thought of that?

Well, I was still drawing with a pen and ink when I started. I got my first computer in my last year at university in 1997. I just happened to be sharing a house with a couple of guys who were doing computing and they helped me build a computer, and they had a copy of 3D Max - I think version one or two - and I taught myself in the last couple of terms and produced my final project with it.

I was fortunate really to have that opportunity to experiment with something which hadn’t really been used in architecture much at all. There were a couple of rendering houses in London who were doing stuff from a purely visualization perspective, but I don’t know of any practices that were using it as a design tool.

That experience got me my first job in terms of the project work I was able to create with it. And we’ve been trying to take advantage of this tech and seeing

how it can open up new possibilities ever since.

And now you are doing… how do you describe it, unexpected architecture?

Well, we’ve always been really interested in ideas and approaching projects from first principles. We’ve worked in China for a while now, and no two cities or regions are the same. And they’ve all got their very

particular history and cultures. So, like many other architects, that’s what we’re interested in. We try and find those moments in their history or those objects

in their art, which we see as potentially exciting as a stepping-off point for an architectural concept.

We never know where we are going to start. There’s no signature style that we fall back on. We try and start fresh each time. And so, we say it’s ‘unexpected’ because we certainly don’t know where it’s going to end up.

We’ve been really lucky with our clients in that they’ve come to us really looking for something new, and they push us in terms of finding these kind of ideas or introducing us to elements of their culture which maybe aren’t readily available. This can lead us to some really incredible discoveries, which we then use to best of our skills and ability to try and generate ideas. It’s trying to keep it fresh and giving them something which no one was really expecting.

Of course, China and the Middle East seem to be the places that really allow architects to go back and find a central story and then do something quite dramatic from it?

Before working in China, most of the work I’d done was UK based. It’s always a challenge in the UK to try and do something new. You’re extremely fortunate if you find a client who wants to push boundaries in terms of design and ideas. It was the opposite starting to work

in China where they were very keen on renewing the way that the world was perceiving them.

The first project I did over there was in 2010, and there were other practices who were working there. Zaha Hadid had recently completed her opera house in Guangzhou, which was a very ‘Zaha’ building to look at.

But this particular client didn’t want Western-imported ideas. They very much wanted us to give them something which was born of the local culture, which was an easily recognizable symbol to their audience and not something abstract or from a Western approach to design.

And so, for us, the main challenge that we set ourselves was ‘how do we deliver these clearly identifiable symbols without them being pastiche or a kind of Disneyfied addition to a normal building?’

So, for us it was really about trying to find a way of expressing these ideas, whether it’s a lantern or bamboo, or silk, finding an architectural language that could express them, whilst having its own integrity as a piece of modern design. It was to give them that very recognizable object but also to some degree to satisfy ourselves architecturally.

When you look at the way we’ve approached it, we try to combine a Western sensibility in terms of trying to come up with a rational approach, which has a degree of abstraction, but still giving them something playful and imaginative. And you can see the results.

You always have to compromise. Sometimes with some of these projects, we’ve been pushed to deliver something a bit more obvious than we perhaps would’ve liked, and some of them have become a bit literal - but on the whole we’re sure the client has been pleased with the output and that’s what is important for us really.

So where is architecture going? We are entering a time of maybe global recession now. Have we seen the end of the boom of the luxurious theater building that transcends all boundaries?

Well it certainly paused in China. I think they’re coming back, and we’ve seen that there’s some interesting work happening over there. But certainly, where we’re currently working in the Middle East and Saudi Arabia, they are pushing the boundaries in a way which has been for us, even with our experience, quite unexpected - in their ambition and their openness to new ways of thinking, new ways of approaching things.

I can see some incredible work coming out of there in the next few years. And when you look at the roster of names who are working over there at the moment, it’s some of the more creative practices working today, and they’re being given opportunities which just aren’t possible anywhere else in the world currently. So, I think it’s going to be great, certainly where we are focused.

And another element of that design in particular is the canopy above it, which on the one hand symbolizes the leafy canopy that exists at the top of a bamboo forest. But at the same time it is also a passive shading device over the entire building.

On some of these buildings, we’ll work on the plans and the conceptual layout, but quite often on Chinese projects these areas are adopted by the local design

institute to develop in detail. Consequently our influence on them often doesn’t run quite as deep as we would ideally like. Where we do maintain influence, particularly on the cladding and surface treatment, we always endeavour to incorporate passive, energy efficient design.

For example, a lot of the work we have produced in China has required large areas of glazing, however we’ve generally tried to include a secondary layer that

articulates the conceptual idea whilst enabling views and passive shading.

It’s the same with the theater in Guangzhou. That entire facade appears to be solid, however the cladding panels are finely perforated allowing occupants on the inside to see out. As a shading device, the panels are incredibly efficient. Where we can, passive shading is something that we try to embed as a first principle in the way we approach façade design.

We’ve just seen cataclysmic weather here in New Zealand, and Europe of course is seeing the most incredibly warm winter, does architecture have to start, not just reflecting the environmental needs of the future, but perhaps trying to influence and create a better future?

More often than not the briefs we receive have environmental criteria which the design has to meet. So, our approach since we started, has always been to

try to find solutions which are embedded in a way of approaching the manufacturing of the final object and

its impact on the environment.

So, for example, if you look at something like the theater in Wuxi, which has some very large expanses of glass, we developed a screen from an array of steel columns that represent bamboo that provide yearround shade; this has a tangible impact on lowering the HVAC load whilst helping to keep the building cool, whilst at the same time embodying the concept for the building.

That’s talking about reducing the environmental impact of the building itself. But can you see a future where the building is actually reaching out and changing the environment around it?

We’ve always been interested in kinetic design as a potential shading device and means for the building or structure to become expressive and provide

entertainment value. We see it as an opportunity to combine sustainability with artistic expression.

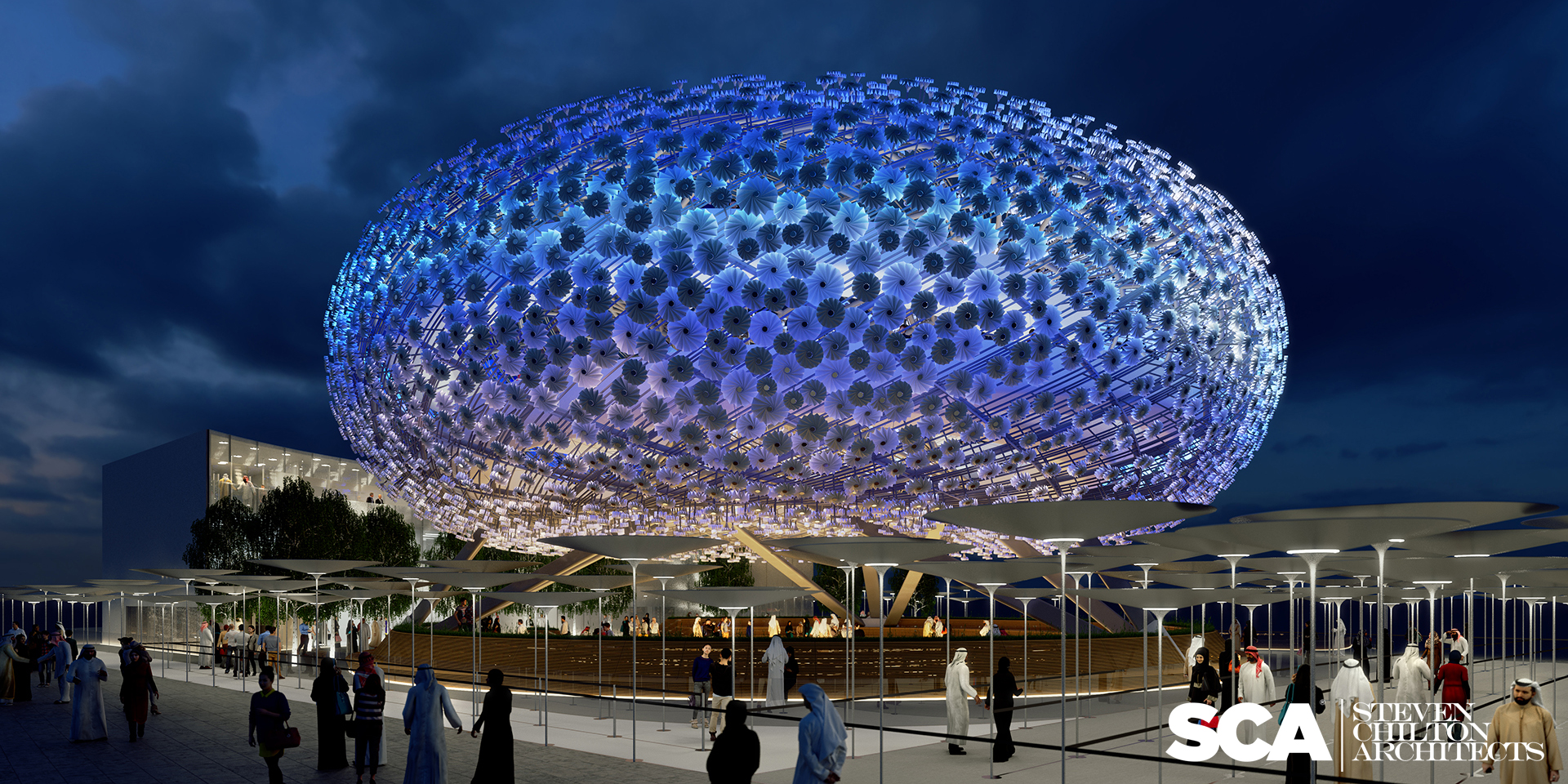

We created a proposal for the U.K. 2020 Expo Pavilion that was conceived to celebrate the countries achievements in the field of AI and space technology. The design included a large steel lattice in the form of a torus covered with thousands of small, flower like objects representing satellites - that opened and closed. These objects provided passive shading to the visitors whilst entertaining them as an interactive façade.

The idea included the use of machine learning and sensors to optimise the flow of visitors whilst giving them an unforgettable, immersive experience.

We worked with a scientist and engineer from Cambridge University to help develop the mechanisms we proposed. In addition to being sustainable and kinetic, the experience would draw attention to the UK’s work in the field of AI, for example it’s application within the agriculture industry to help farmers decide how best to plant their fields at certain times of the year.

There’s a whole field of interest where those two technologies intersect, which we try to express through the building as a kind of storytelling machine. As buildings become smarter and sensors that monitor the environment more sophisticated, intelligent systems capable of analysing enormous quantities of data in real time will contribute to ensuring the built environment uses energy with ever

greater efficiency.